An Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator, or ICD, is a device that helps to keep the heart beating regularly in order to prevent sudden cardiac arrest. It is implanted under the skin in the chest area, and it works by sending electrical pulses to the heart if an irregular heartbeat is detected. An ICD can help to prevent sudden cardiac death in people who are at risk for this type of event.

As someone who has lived with an ICD for just over 18 months, I can understand that reading about this device for the first time can seem somewhat intimidating and overwhelming. But I’m here for you – if you or a loved one have been told by your doctor that you may need to consider getting an ICD, this post will provide you with everything you need to know about this life-saving device and what it’s like living with one.

Disclaimer: This is not medical advice, if you have questions related to heart disease, please talk to your medical practitioner. If you are experiencing an emergency such as chest pain, please call an ambulance.

What is an Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator (ICD), and How Does it Work?

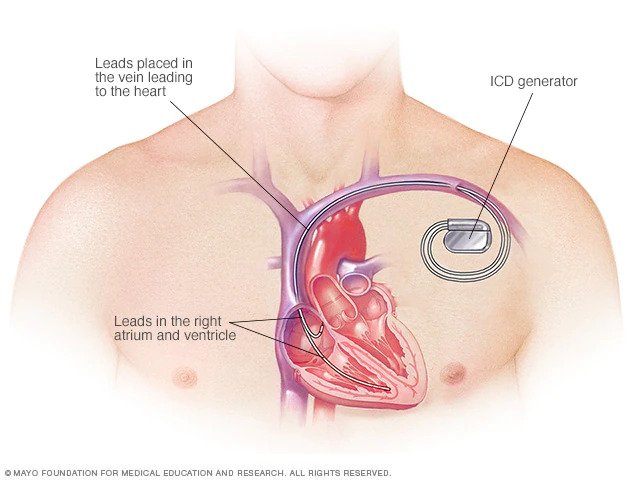

Implantable cardioverter defibrillators are devices that help to regulate irregular heartbeats. ICD’s are a small, battery-powered device that is implanted under the skin in the upper chest area and are typically about the size of a stopwatch. ICDs work by sending electrical pulses to the heart if an irregular heart rhythm is detected.

These electrical pulses help to keep the heart beating regularly and can prevent sudden cardiac death in people who are at risk for this type of event. There are 2 types of implantable cardioverter defibrillators:

- A traditional ICD is implanted in the chest, and the wires (leads) connect to the heart. The implant procedure requires invasive surgery.

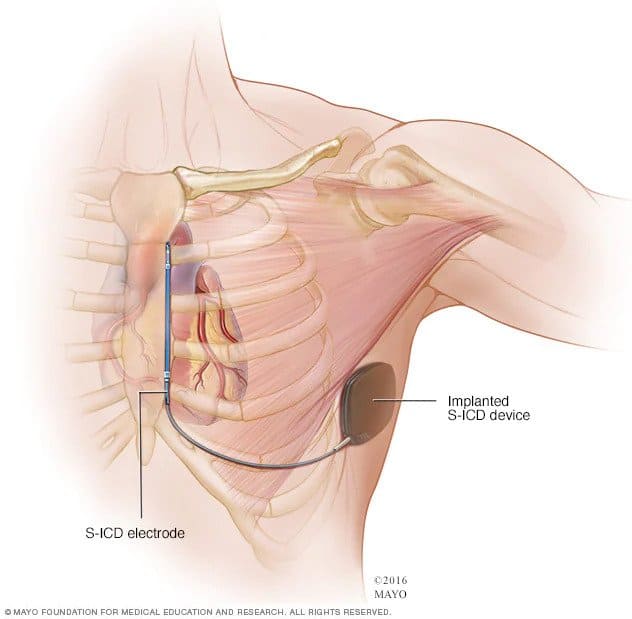

- A subcutaneous ICD (S-ICD) Another approach is a tiny device implanted under the skin at the side of the chest below the armpit. It’s linked to an electrode that runs down along the breastbone. An S-ICD is larger than a normal ICD but does not connect to the heart.

An implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) can also be programmed to function as a basic pacemaker if required. Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) is an electrical cardioversion procedure to treat bradycardia, a heart rhythm problem in which the heart does not beat fast enough (slow heart rhythm). The implantable cardioverter defibrillator can act as a pacemaker any time the heart rate drops below a preset rate.

Who may need an Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator (ICD)?

An Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator (ICD) may be recommended for people who have survived cardiac arrest or people who have congenital heart disease or other related underlying conditions, in order to prevent sudden death as a result life threatening ventricular fibrillation – this is done by administering device based therapy (electric shock). Sudden cardiac arrest is often caused by an irregular heart rhythm (ventricular fibrillation).

To summarise, people who are at high risk for sudden cardiac arrest and may need an implantable cardioverter defibrillator include those who have/have had:

- A heart attack

- Abnormal heart rhythm/cardiac rhythm abnormalities (arrhythmia)

- Cardiac arrest (when the heart suddenly stops beating)

- Congenital heart disease such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

What’s Involved in the Surgery?

The surgery to implant an implantable defibrillator (ICD) is usually done as a day surgery procedure, which means you will be able to go home the same day.

The surgery takes about an hour, and you will be given general anesthesia to keep you asleep during the procedure. Once you are asleep, the surgeon will make a small incision in your chest and insert the ICD under your skin. The surgeon will then attach the leads (wires) from the implantable defibrillator to your heart.

After the surgery is complete, you will be taken to a recovery room where you will be monitored until the anesthesia has worn off. You can expect to experience some soreness and bruising around the incision area after the surgery.

In some cases, people stay in hospital overnight for observation and are discharged the following day.

Risks Following Surgery

Risks following surgery are low, but as with any surgery, there are potential risks and complications. These include:

- Infection at the incision site

- Bleeding, bruising, or swelling around the incision site

- Damage to blood vessels or nerves during surgery

- Allergic reaction to anesthesia

- Blood clotting

- Heart rhythm problems immediately after surgery (this is usually temporary and will resolve on its own).

- Dislodging of the leads, requiring another procedure to reposition the leads

How to prepare for Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator (ICD) Surgery

You will be asked to stop eating or drinking after midnight on the night before your surgery. This is because you will be given general anesthesia, which can cause nausea and vomiting.

You should also avoid drinking alcohol for 24 hours before the surgery as it can thin your blood and increase bleeding during the procedure.

Be sure to let your surgeon know if you are taking any blood-thinning medication such as aspirin or warfarin (Coumadin) or have any other medical conditions that could affect the procedure. You may be asked to stop taking these medications a week or so before the surgery.

Prior to surgery, healthcare providers usually perform several tests. These include:

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). An MRI may be performed in order to establish a clear picture of the heart and see if there is any scarring around the heart muscle (certain conditions).

- Electrocardiography (ECG or EKG). The electrical activity of the heart is measured by an ECG, which is a fast and painless test for measuring cardiac electrical signals. Sticky patches (electrodes) are placed on the chest as well as a few other body parts, including the arms and legs. The electrodes are linked to a computer that displays the results of the test.

- Echocardiography. The cardiac echocardiogram is a noninvasive test that creates moving images of the heart using sound waves. It displays the size and structure of the heart as well as how blood flows through it.

- Holter monitoring. A Holter monitor is a small, portable device that monitors the heart rhythm. It may be able to spot irregular heart rhythms that an ECG missed. You’ll typically wear a Holter monitor for 1-2 days. Sensors on your chest connect (through wires) to a battery-operated recording device carried in a pocket or worn on a belt or shoulder strap. You may be asked to keep a diary of your activities and symptoms while wearing the monitor. Your health care provider will usually compare the diary with the electrical recordings and attempt to discover the source of your problems.

- Event recorder. If you didn’t have any irregular heart rhythms while you wore a Holter monitor, your health care provider may recommend an event recorder. There are several different types of event recorders, which can be worn for a longer time. Event recorders are similar to Holter monitors and generally require you to push a button when you feel symptoms.

- Electrophysiology study (EP study). The health care provider guides a flexible tube (catheter) through a blood vessel into the heart. More than one catheter can often be used in the blood vessel. The tiny electrodes on the tips of each catheter send signals and record the heart’s electrical activity. This data is used by a medical professional to determine which section of the heart is producing the irregular rhythm.

What Happens if You Receive an ICD Shock?

If the implantable cardioverter defibrillator delivers an electric shock, it means that your heart has gone into a life-threatening arrhythmia usually as a result of dangerously fast heart rhythms, and the ICD responds by delivering a treatment shock to restore a normal heart rhythm.

Most people say that receiving an ICD shock feels like being hit in the chest with a baseball bat or being kicked in the chest. It can be painful, but it is not harmful and is often lifesaving.

You may also feel dizzy or lightheaded after receiving a shock from your ICD. It is important to remember that the ICD shocks are only delivered when they are needed. Once you receive a shock, you should do your best to remain calm, practice deep breathing techniques and call your healthcare provider.

In general, driving is not an issue if you have an implantable cardioverter defibrillator, however, healthcare providers may provide some guidelines specific to you depending on your situation.

You should not drive if you feel lightheaded or dizzy after receiving an electric shock from your ICD and in some countries, the advice is not to drive at all following an electrical shock until you see your healthcare provider.

If you experience symptoms while driving, pull over to the side of the road and call for help.

Living with an Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator (ICD)

Once you have fully recovered from surgery and been discharged from the hospital, you can return to your normal activities. There are a few things to keep in mind when living with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator:

You will need to avoid contact sports or any activity that could cause significant trauma to your chest as this could damage the ICD leads.

If you experience symptoms such as dizziness, lightheadedness, fainting or chest pain, you should stop what you are doing and rest in case these symptoms are a result of life threatening arrhythmias. If symptoms persist, call for medical help.

Be sure to keep all follow-up appointments with your healthcare provider and cardiologist so they can monitor your ICD and make any necessary adjustments. This may include an appointment once every 6 months or annually (depending on what the healthcare provider recommends) with the ICD company representative to review results that were recorded on the ICD.

It is also important to carry an ID card or wear medical alert jewelry that states you have an Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator. This will ensure that you receive the proper medical care if you are involved in an accident or have a medical emergency.

It’s important to acknowledge that whilst many people feel no symptoms and carry on with life as usual, some people may find living with a condition that requires an Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator overwhelming, and/or may find it difficult managing the stress/anxiety that comes with being told they are at risk of sudden death (funnily enough).

If you fall into that category, please know that there is support available – talk to your healthcare provider about getting a referral to see someone who can teach you coping and breathing techniques to assist in calming you down if you become conscious of your heart rate.

Diet and exercise with an Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator (ICD)

Just like anyone else, it is important to eat a healthy diet and exercise regularly if you have an Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator.

Eating a healthy diet helps to maintain a healthy weight, reduces cholesterol and blood pressure, and can help control blood sugar levels.

Exercise has many benefits including reducing stress, improving mood, and helping to control weight.

It is important to talk to your healthcare provider before starting or changing your exercise routine as they can provide guidance on what types of activities are safe for you to do.

If you are concerned about experiencing an overly-fast heart rate during exercise, ask your healthcare provider about cardiovascular medicine options available to you such as beta blockers.

My Experience with an Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator (ICD)

I learned when I was 17 years old that I had hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) which is where the heart muscle becomes abnormally thick, which makes it hard for the heart to pump blood.

My health care provider at the time explained to me that this condition put me at high risk of experiencing cardiac arrest, potentially leading to sudden death.

At the time I found out, I was extremely into sports – playing on 2 different soccer teams and the school basketball team. I was basically told that unless I had the ICD implanted, it would be risky, for example, to walk up a hill with a heavy backpack on.

This was devastating news for me, as at the time, I was also considering a career in sport. Once I learned this information, I did my best to avoid the topic of sport as it hurt too much.

I started to become symptomatic to the abnormal heartbeat (especially ventricular tachycardia) – every now and then, I could feel my heart beating abnormally – I would become nervous, which increased my heart rate (hit of adrenaline) and that made me feel extremely anxious and worried until I could feel the heart rate return to normal. It’s a horrible cycle.

I did not want to go through with the ICD implantation initially because when I learned of the risks (related to the surgery), the size of the ICD device, the fact that it was a battery powered device (meaning at some point, the battery would need to be replaced) and the fact that potentially, the ICD delivers a shock if you experience ventricular tachycardia (the dangerous rhythm), I decided to wait a few years until there were developments in the implanted cardiac devices industry before I would consider going through with the ICD procedure.

The waiting game was hard – I learned that for me personally, stress and my emotional state had a large part to play in how my body would react to these episodes of ventricular arrhythmia. If I experienced an episode, I would find myself physically beating my chest (attempting to mimic a shock from an ICD) until I could feel a normal heartbeat again. I learned some deep breathing and focus techniques to counter the hit of adrenaline I would get during these episodes.

10 long years after initially learning of the condition and being recommended the ICD implantation, I decided to go through with the procedure. I had put a lot of thought into it throughout the years, and I eventually decided that the benefits outweighed the drawbacks. I especially missed being able to exercise with confidence.

The actual surgery went smoothly, so I didn’t experience any issues there. At first, I was very conscious of the ICD being in my chest. I was worried about lying down on my left side in case the wires dislodged, or the pressure of the ICD pressing on my chest would be painful. However, after a few weeks had passed, I barely noticed the ICD was even there most of the time. There is no discomfort and it doesn’t affect any other aspect of my life. I remember one thing I was worried about was getting on flights and going through security, as traveling around is a big part of my job. But I can tell you now, I have had absolutely no issues there and I’ve been on several flights. The same goes with walking into shops with those security alarm gates – I’ve never had issues there either.

Once I could start exercising again (I believe it was a few weeks following the surgery), I chose to swim – this was purely because I learned that with swimming, I could more accurately control the intensity of the exercise and therefore, keep my heart rate (reasonably) low. It was the first time I had exercised in over 10 years other than some brisk walking. What a feeling that was – to swim with confidence.

Since then, I began swimming on a regular basis – and I even play badminton on weekends. I have found that with a combination of the exercise and the feeling of confidence/security I have as a result of receiving the ICD procedure, I have never felt better in my life.

Conclusion

In summary, Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillators are life-saving devices that can be a bit overwhelming to manage at first, but with a little adjustment time and the right support, you can live a full and active life. If you are considering an ICD implantation, talk to your healthcare provider about what’s involved and whether it’s the right choice for you.

If you have any questions or would just generally like to reach out and have a chat, please don’t hesitate to contact me by completing the form on the contact page.

Thank you.

Disclaimer: This is not medical advice, if you have questions related to heart disease, please talk to your medical practitioner. If you are experiencing an emergency such as chest pain, please call an ambulance.